激素宫内节育器

| 激素宫内节育器 | |

|---|---|

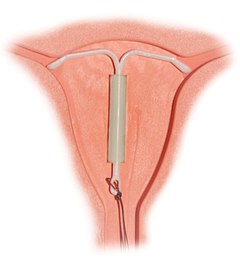

正確置入的宮內節育器 | |

| 背景 | |

| 生育控制種類 | 宫内节育器 |

| 初次使用日期 | 1990 (Mirena—現仍在使用) 1976 (Progestasert—於2001停用) |

| 失敗比率 (置入後第一年) | |

| 完美使用 | 0.1–0.2% |

| 一般使用 | 0.1–0.2% |

| 用法 | |

| 持續期間 | 3–8年 |

| 可逆性 | 2–6月 |

| 注意事項 | 每月檢查線繩位置 |

| 醫師診斷 | 一個月後複查,此後每年至少複查一次 |

| 優點及缺點 | |

| 是否可以防止性傳播疾病 | 否 |

| 週期 | 月經不規則,經血通常較少,或無月經 |

| 是否影響體重 | 可能的副作用 |

| 好處 | 无需每日采取避孕腊施 |

| 風險 | 良性卵巢囊腫、骨盆腔發炎、子宮穿孔(罕見)等 |

激素宮內節育器(hormonal intrauterine device)常見者為含孕激素子宮內系統(intrauterine system (IUS) with progestogen),商品名有 Mirena(蜜蕊娜、曼月乐)等,是一种可以释放激素(如屬於孕激素的左炔諾孕酮)的宫内节育器[1],其用途包括避孕、缓解月经过多、预防雌激素替代疗法可能产生的子宫内膜增生等[1]。

含孕激素IUD是最有效的避孕方法之一,年避孕失败率約為0.2%[2]。该装置经由手术放入子宫中,有效期为3到8年[3][4]。取出之后,生育能力将很快恢复[1]。

使用此裝置的副作用有經期不規則、良性卵巢囊腫、骨盆腔疼痛和憂鬱[1]。罕見案例有子宮穿孔[1]。不建議個體於懷孕期間使用,但母乳哺育期間使用對於嬰兒屬於安全[1]。含孕激素IUD是一種長效且可逆的避孕方法[5]。作用機制是通过孕激素以稠化宫颈黏液并让子宫内膜变薄,从而抑制精子通过宫颈并影响受精卵着床,偶爾也會抑制排卵,借由這些機制起到避孕的作用[1]。

含左炔諾孕酮的IUD於1990年在芬蘭首次獲准用於醫療用途,並於2000年獲准在美國使用[6]。此裝置已列入世界衛生組織基本藥物標準清單之中[7][8]。

醫療用途

[编辑]| 臨床資料 | |

|---|---|

| 懷孕分級 | |

| ATC碼 |

|

| 法律規範狀態 | |

| 法律規範 |

|

含孕激素IUD是一種極其有效的避孕方法,於2021年所做的一項研究顯示它可用於緊急避孕[15]。含孕激素IUD除用於避孕之外,還用於預防和治療:

- 經血過多[16]

- 子宮內膜異位症和慢性骨盆腔疼痛[16][17]

- 子宮腺肌病和經痛[16][18]

- 貧血[19]

- 子宮內膜增生症(特別是對希望在治療子宮內膜增生症的同時仍保持生育能力的更年期前女性)[20][21]

- 在某些情況下,使用含孕激素IUD可避免進行子宮切除術[22]。

優點:

- 為最有效且可逆的避孕法之一[23]

- 個體於母乳哺育期間可使用[24]

- 無性行為前準備事項,[25]但建議用者和醫師定期檢查裝置的線繩,以確保其位置正確[26]

- 希望再度懷孕的用者在移除裝置後的24個月內有90%能成功懷孕[27]

- 可能經血變少(有些女性的月經甚至完全停止)[28]

- 有效期長達3至8年(依含孕激素IUD種類而異)[4]

缺點:

有效性

[编辑]使用商品名為Mirena的裝置可有效避孕長達8年[29]。使用商品名為Kyleena的裝置,有效期為5年,而使用商品名為Skyla的裝置,有效期為3年[30][31]。

含孕激素IUD是一種長效且可逆的避孕法,被認為是最有效的避孕方式之一。此裝置的第1年失敗率為0.1-0.2%,5年失敗率為0.7-0.9%[32][29][33]。此類失敗率與輸卵管結紮技術相當,但不同點是含孕激素IUD的做法為可逆。

含孕激素IUD被認為比其他常見的可逆避孕法(如複合口服避孕藥)更有效,因為用者於置入之後幾乎不必做任何事[23]。其他避孕法的效果會受到用者本身的作為而降低,如服藥時間不準。使用含孕激素IUD後毋須每日、每週或每月服藥,因此其典型使用失敗率與完美使用失敗率相同[23]。

在一項為期10年的研究中,發現使用含左炔諾孕酮IUD在治療經血過多方面與口服藥物(如傳明酸、甲芬那酸、雌激素與黃體素複合製劑或單純孕激素)的效果相當,前述女性未因經血過多而需進行手術,且生活品質仍獲得改善[34][35]。

有雙角子宮的女性若需避孕,通常會放置兩個IUD(每個角一個),因只做單一子宮角放置的避孕效果尚無足夠實證支持[36]。目前尚無充分的科學證據支持將含孕激素IUD用於治療雙角子宮個體的經血過多。然而有部分個案報告顯示,單一含孕激素IUD在治療此類個體方面具有一定的療效。[37]。

母乳哺育

[编辑]含孕激素的避孕方法(例如IUD)被認為不會影響母乳供應或嬰兒生長[38]。然而在Mirena申請DA核准的研究中發現使用此種含孕激素IUD的母親有44%於75天後仍繼續哺乳,低於使用銅質IUD的母親 (79%於75天後仍繼續哺乳)[39]。:37

使用Mirena的個體,約有0.1%的左炔諾孕酮會通過母乳傳遞給哺乳嬰兒[40]。一項針對母親使用單純左炔諾孕酮避孕法的哺乳嬰兒進行的為期6年研究,發現這些嬰兒患呼吸道感染和眼部感染的風險較母親使用銅質IUD的嬰兒為高,但神經系統疾病的風險較低[41]。目前尚無任何長期的研究來評估母乳中左炔諾孕酮對嬰兒在長期方面的影響。

對於哺乳中的母親,美國疾病管制與預防中心(CDC)建議激素避孕法並非首選。不過,如果選擇使用像Mirena這樣僅含孕激素避孕器,建議只有在評估後,認為益處大於風險時才適合使用,在使用期間也須密切觀察身體狀況[42]。世界衛生組織(WHO)建議避免個體於產後立即置入,理由是裝置從子宮脫落的比率會增加。WHO對產後6週內母親使用Mirena,可能對嬰兒肝臟和腦部發育造成的潛在影響表示擔憂,並強調需要更多的研究來評估其安全性。然而WHO建議從產後6週開始,即使是哺乳婦女,也可用Mirena作為避孕選項[43][44]。非營利組織美國計劃生育聯合會則建議可在產後4週即開始為哺乳婦女提供Mirena作為避孕選項[45]。

禁忌症

[编辑]個體有以下的情況即不應使用含孕激素IUD:

- 懷孕中或懷疑已懷孕者[24]

- 有不明原因的異常陰道出血者[24](此點有爭議)[46]

- 患有未經治療的子宮頸癌或子宮癌者[24]

- 患有或可能患有乳癌者[24]

- 子宮頸或子宮異常者[47](此點有爭議)[46]

- 近三個月內曾患有骨盆腔發炎者[24]

- 近三個月內曾感染性傳染病者(如披衣菌感染或淋病)[24]

- 患有肝病或腫瘤者[47]

- 對左炔諾孕酮或裝置中任何非活性成分過敏者[47]

進行子宮擴張與刮除術(D&E)人工流產(中期妊娠終止)後的個體可裝置IUD,但可能會增加裝置從子宮脫落比率[48]。為降低感染風險,不建議在以下情況下進行IUD置入: 1. 接受藥物流產後,尚未進行超音波檢查以確認流產已完全。 2. 接受藥物流產後,尚未出現第一次月經[45]。

完整的禁忌症清單可在世界衛生組織避孕藥物使用醫學適應症標準(Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use)和CDC美國避孕藥物使用醫學適應症標準(United States Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use)中取得[24][49]。

副作用

[编辑]- 經期不規則、[50][51][52]

- 痙攣和疼痛、[53]

- 裝置脫落、 [53][54][55][56][57]

- 子宮穿孔、[58][56]

- 懷孕併發症、[39]:3–4[53][54][53][54][39]:5,41

- 感染、[59][53]

- 卵巢囊腫、[60][61]

- 精神健康變化,(包括神經緊張、情緒低落、情緒波動)、[47]

- 體重增加、[47]

- 頭痛或偏頭痛、[47]

- 噁心、[47]

- 痤瘡、[47]

- 毛髮過多、[47]

- 下腹或背部疼痛、[47]

- 性慾減退、[47]

- 陰道瘙癢、發紅或腫脹、[47]

- 陰道產生分泌物、[62]

- 乳房疼痛、壓痛、[62]

- 水腫、[62]

- 腹脹、[62]

- 子宮頸炎、[62]

- 細菌性陰道病、[63]

- 可能會影響葡萄糖耐受性、[62]

- 可能會出現視力變化或隱形眼鏡耐受性改變、[27]

- 可能會導致維生素B1缺乏,影響精力、情緒和神經系統功能、[27]

- "線繩消失" - 指婦女在例行檢查時無法觸摸到IUD的線繩,且在膣鏡檢查下也無法看到[64][65]。

癌症

[编辑]根據國際癌症研究機構 (IARC) 於1999年對僅含孕激素避孕法進行的評估,有一些證據顯示此避孕法可降低子宮內膜癌的風險。IARC於1999年的研究結論,表示沒證據表明僅含孕激素的避孕法會增加任何癌症的風險,但所做研究的規模太小,無法取得確定結論[66]。

骨質密度

[编辑]沒證據顯示Mirena會影響用者的骨質密度[67]。兩項針對前臂骨質的小型研究顯示密度並下降[68][69]。

組成與激素釋放

[编辑]

含孕激素IUD是一種小的T形塑料裝置,含有左炔諾孕酮,[29]微量左炔諾孕酮會逐步釋放進入子宮(主要是旁分泌,而非全身性),其中大部分留在子宮內,有少量會進入身體其他部位[53]。

置入與移除IUD

[编辑]圖片說明(由左至右):

1. 將MirenaIUD置入陰道的超音波掃描示意圖。

2. 置入含孕激素IUD

3. 移除含孕激素IUD

作用機轉

[编辑]左炔諾孕酮是一種孕激素受體激動劑。最新的研究顯示含孕激素IUD的主要避孕機制是防止卵子受精[53][70][71][72][73]

歷史

[编辑]

銅質IUD在1960年代和1970年代開發上市,而含孕激素IUD於1970年代開發成功[74]。於芝加哥邁克爾·里斯醫院服務的安東尼奧·斯科門加醫生(Dr. Antonio Scommenga)發現,在子宮內施用孕酮具有避孕功效[74]。芬蘭醫生約尼·瓦爾特·塔帕尼·盧卡伊寧根據安東尼奧·斯科門加醫生的發現而製造可釋放孕酮的T形IUD,於1976年以Progestasert System商品名稱上市。第一代子宮內避孕器使用壽命很短,只有1年,市場表現不佳。盧卡伊寧醫生後來改用左炔諾孕酮,研發出可持續使用5年的Mirena,大幅提升避孕器的效用[75]。

FDA於2013年核准商品名稱為Skyla的避孕器上市(為一種有效期長達3年的低劑量左炔諾孕酮IUD)[76]。Skyla造成的月經模式與Mirena不同,臨床試驗中,使用Skyla者只有6%出現閉經(而使用Mirena者約有20%會出現)。

目前Mirena避孕器系列僅在芬蘭生產[77]。

爭議

[编辑]Mirena的製造商拜耳公司因誇大產品功效、淡化使用風險以及對該裝置進行"虛假或誤導性陳述"而收到美國食品藥物管理局警告信[78][79]。美國聯邦機構在2000年到2013年期間收到超過70,072份關於該裝置和相關不良反應的投訴[80][81]。截至2014年4月,美國已有超過1,200件對此裝置興起的法律訴訟[79][82][83][84]。

參考文獻

[编辑]- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 British National Formulary: BNF 69 69th. British Medical Association. 2015: 556. ISBN 978-0-85711-156-2.

- ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

Trus2011的参考文献提供内容 - ^ Levonorgestrel intrauterine system medical facts from Drugs.com. drugs.com. [2017-01-01]. (原始内容存档于2017-01-01).

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Hormonal IUDs. www.plannedparenthood.org. [2019-04-20]. (原始内容存档于2019-04-24) (英语).

- ^ Wipf J. Women's Health, An Issue of Medical Clinics of North America. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2015: 507 [2017-09-01]. ISBN 978-0-323-37608-2. (原始内容存档于2023-01-10).

- ^ Bradley LD, Falcone T. Hysteroscopy: Office Evaluation and Management of the Uterine Cavity. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2008: 171 [2017-09-01]. ISBN 978-0-323-04101-0. (原始内容存档于2023-1-12).

- ^ World Health Organization. World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2019. hdl:10665/325771

. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ World Health Organization. World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2021. hdl:10665/345533

. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^ 9.0 9.1 Mirena (levonorgestrel) intrauterine device. Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 2024-07-17 [2024-10-12].

- ^ Mirena Product information. Health Canada. 2007-11-22 [2024-04-19]. (原始内容存档于2024-04-19).

- ^ Mirena - levonorgestrel intrauterine device. Bayer Health Pharmaceuticals. May 2009 [18 June 2015]. (原始内容存档于18 June 2015).

- ^ Kyleena- levonorgestrel intrauterine device. DailyMed. 13 March 2023 [2024-04-19]. (原始内容存档于2023-09-22).

- ^ Skyla- levonorgestrel intrauterine device. DailyMed. 2023-01-31 [2024 -04-19]. (原始内容存档于2023-12-09).

- ^ Liletta- levonorgestrel intrauterine device. DailyMed. 2023-06-29 [2024-04-19]. (原始内容存档于2021-11-29).

- ^ Science Update: Hormonal IUD as effective as a copper IUD at emergency contraception and with less discomfort, NICHD-funded study suggests. 4 February 2021 [2021-07-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-07-26).

- ^ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Bahamondes L, Bahamondes MV, Monteiro I. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system: uses and controversies. Expert Review of Medical Devices. July 2008, 5 (4): 437–445. PMID 18573044. S2CID 659602. doi:10.1586/17434440.5.4.437.

- ^ Petta CA, Ferriani RA, Abrao MS, Hassan D, Rosa E, Silva JC, Podgaec S, Bahamondes L. Randomized clinical trial of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and a depot GnRH analogue for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain in women with endometriosis. Human Reproduction. July 2005, 20 (7): 1993–1998. PMID 15790607. doi:10.1093/humrep/deh869

.

.

- ^ Sheng J, Zhang WY, Zhang JP, Lu D. The LNG-IUS study on adenomyosis: a 3-year follow-up study on the efficacy and side effects of the use of levonorgestrel intrauterine system for the treatment of dysmenorrhea associated with adenomyosis. Contraception. March 2009, 79 (3): 189–193. PMID 19185671. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2008.11.004.

- ^ Faundes A, Alvarez F, Brache V, Tejada AS. The role of the levonorgestrel intrauterine device in the prevention and treatment of iron deficiency anemia during fertility regulation. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. June 1988, 26 (3): 429–433. PMID 2900174. S2CID 34592937. doi:10.1016/0020-7292(88)90341-4.

- ^ The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee Opinion no. 631. Endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia. Obstetrics and Gynecology. May 2015, 125 (5): 1272–1278. PMID 25932867. S2CID 46508283. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000465189.50026.20.

- ^ Mittermeier T, Farrant C, Wise MR. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for endometrial hyperplasia. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. September 2020, 2020 (9): CD012658. PMC 8200645

. PMID 32909630. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012658.pub2.

. PMID 32909630. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012658.pub2.

- ^ Marjoribanks J, Lethaby A, Farquhar C. Surgery versus medical therapy for heavy menstrual bleeding. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. January 2016, 2016 (1): CD003855. PMC 7104515

. PMID 26820670. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003855.pub3.

. PMID 26820670. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003855.pub3.

- ^ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Buckel C, Madden T, Allsworth JE, Secura GM. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. The New England Journal of Medicine. May 2012, 366 (21): 1998–2007 [2019-06-30]. PMID 22621627. S2CID 16812353. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110855

. (原始内容存档于2020-06-11). 已忽略未知参数

. (原始内容存档于2020-06-11). 已忽略未知参数|df=(帮助) - ^ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 24.6 24.7 Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, Berry-Bibee E, Horton LG, Zapata LB, Simmons KB, Pagano HP, Jamieson DJ, Whiteman MK. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016 (PDF). MMWR. Recommendations and Reports. July 2016, 65 (3): 1–103 [2020-02-03]. PMID 27467196. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6503a1

. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2020-10-16).

. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2020-10-16).

- ^ IUD. Planned Parenthood. [2015-06-18]. (原始内容存档于2015-06-18).

- ^ Convenience. Let's Talk About Mirena. Bayer. [2015-06-18]. (原始内容存档于2015-06-18).

- ^ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Mirena. MediResource Inc. [2015-06-18]. (原始内容存档于2015-07-03).

- ^ 28.0 28.1 Hidalgo M, Bahamondes L, Perrotti M, Diaz J, Dantas-Monteiro C, Petta C. Bleeding patterns and clinical performance of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena) up to two years. Contraception. February 2002, 65 (2): 129–132. PMID 11927115. doi:10.1016/s0010-7824(01)00302-x.

- ^ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Mirena IUD Homepage | Official Website. [2012-07-19]. (原始内容存档于2012-07-31)., Bayer Pharmaceuticals.

- ^ Highlights of Prescribing Information (报告). 2013-01-09. (原始内容存档于2016-05-06). 已忽略未知参数

|df=(帮助) - ^ What are hormonal IUDs?. Planned Parenthood. [2019-04-19]. (原始内容存档于2019-04-24).

- ^ Westhoff CL, Keder LM, Gangestad A, Teal SB, Olariu AI, Creinin MD. Six-year contraceptive efficacy and continued safety of a levonorgestrel 52 mg intrauterine system. Contraception. March 2020, 101 (3): 159–161 [2 January 2020]. PMID 31786203. S2CID 208535090. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2019.10.010. (原始内容存档于2020-06-10).

- ^ Jensen JT, Creinin MD, Speroff L (编). Speroff & Darney's clinical guide for contraception Sixth. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer. 2019: 15. ISBN 978-1-9751-0728-4. OCLC 1121081247.

- ^ Kai J, Dutton B, Vinogradova Y, Hilken N, Gupta J, Daniels J. Rates of medical or surgical treatment for women with heavy menstrual bleeding: the ECLIPSE trial 10-year observational follow-up study. Health Technology Assessment. October 2023, 27 (17): 1–50 [2024-04-12]. PMC 10641716

. PMID 37924269. doi:10.3310/JHSW0174. (原始内容存档于2023-11-06) (英语).

. PMID 37924269. doi:10.3310/JHSW0174. (原始内容存档于2023-11-06) (英语).

- ^ The coil and medicines are both effective long-term treatments for heavy periods. NIHR Evidence. 2024-03-08 [2024-04-12]. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_62335. (原始内容存档于2024-03-18).

- ^ Oelschlager AM, Debiec K, Micks E, Prager S. Use of the Levonorgestrel Intrauterine System in Adolescents With Known Uterine Didelphys or Unicornuate Uterus. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2013, 26 (2): e58. ISSN 1083-3188. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2013.01.029

.

.

- ^ Acharya GP, Mills AM. Successful management of intractable menorrhagia with a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device, in a woman with a bicornuate uterus. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. July 1998, 18 (4): 392–393. PMID 15512123. doi:10.1080/01443619867263.

- ^ Truitt ST, Fraser AB, Grimes DA, Gallo MF, Schulz KF. Lopez LM , 编. Combined hormonal versus nonhormonal versus progestin-only contraception in lactation. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2003, (2): CD003988. PMID 12804497. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003988.

- ^ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Medical review of NDA 21-225: Mirena (levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system) Berlex Laboratories (PDF). Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. December 2000. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2008-02-27).

- ^ MIRENA Data Sheet (PDF). Bayer NZ. 2009-12-11 [2011-02-10]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2011-07-06).

- ^ Schiappacasse V, Díaz S, Zepeda A, Alvarado R, Herreros C. Health and growth of infants breastfed by Norplant contraceptive implants users: a six-year follow-up study. Contraception. July 2002, 66 (1): 57–65. PMID 12169382. doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(02)00319-0.

- ^ Classifications for Intrauterine Devices | CDC. www.cdc.gov. 2020-04-09 [2020-07-07]. (原始内容存档于2020-07-15) (美国英语).

- ^ World Health Organization. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use 5th. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2015. ISBN 978-92-4-154915-8. hdl:10665/181468

.

.

- ^ World Health Organization. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, fifth edition 2015: executive summary. World Health Organization. 2015 [2020-02-03]. hdl:10665/172915

. (原始内容存档于2021-08-28).

. (原始内容存档于2021-08-28).

- ^ 45.0 45.1 Understanding IUDs. Planned Parenthood. July 2005 [2006-10-08]. (原始内容存档于2006-10-12).

- ^ 46.0 46.1 Heavy menstrual bleeding (update). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2018.

- ^ 47.00 47.01 47.02 47.03 47.04 47.05 47.06 47.07 47.08 47.09 47.10 47.11 Mirena: Consumer Medicine Information (PDF). Bayer. March 2014 [2014-04-27]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2014-04-27).

- ^ Roe AH, Bartz D. Society of Family Planning clinical recommendations: contraception after surgical abortion. Contraception. January 2019, 99 (1): 2–9. PMID 30195718. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.08.016

.

.

- ^ WHO. Intrauterine devices (IUDs). Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use 4th. Geneva: Reproductive Health and Research, WHO. 2010. ISBN 978-92-4-156388-8. (原始内容存档于2012-07-10).

- ^ Hidalgo M, Bahamondes L, Perrotti M, Diaz J, Dantas-Monteiro C, Petta C. Bleeding patterns and clinical performance of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena) up to two years. Contraception. February 2002, 65 (2): 129–132. PMID 11927115. doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(01)00302-X.

- ^ McCarthy L. Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine System (Mirena) for Contraception. Am Fam Physician. May 2006, 73 (10): 1799– [4 May 2007]. (原始内容存档于2007-09-26).

- ^ Rönnerdag M, Odlind V. Health effects of long-term use of the intrauterine levonorgestrel-releasing system. A follow-up study over 12 years of continuous use. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. September 1999, 78 (8): 716–721. PMID 10468065. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0412.1999.780810.x

.

.

- ^ 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 53.4 53.5 53.6 Dean G, Schwarz EB. Intrauterine contraceptives (IUCs). Hatcher RA, Trussell J, Nelson AL, Cates Jr W, Kowal D, Policar MS (编). Contraceptive technology 20th revised. New York: Ardent Media. 2011: 147–191. ISBN 978-1-59708-004-0. ISSN 0091-9721. OCLC 781956734. p.150:

Mechanism of action

Although the precise mechanism of action is not known, currently available IUCs work primarily by preventing sperm from fertilizing ova.26 IUCs are not abortifacients: they do not interrupt an implanted pregnancy.27 Pregnancy is prevented by a combination of the "foreign body effect" of the plastic or metal frame and the specific action of the medication (copper or levonorgestrel) that is released. Exposure to a foreign body causes a sterile inflammatory reaction in the intrauterine environment that is toxic to sperm and ova and impairs implantation.28,29 The production of cytotoxic peptides and activation of enzymes lead to inhibition of sperm motility, reduced sperm capacite journal and survival, and increased phagocytosis of sperm.30,31… The progestin in the LNg IUC enhances the contraceptive action of the device by thickening cervical mucus, suppressing the endometrium, and impairing sperm function. In addition, ovulation is often impaired as a result of systemic absorption of levonorgestrel.23

p. 162:

Table 7-1. Myths and misconceptions about IUCs

Myth: IUCs are abortifacients. Fact: IUCs prevent fertilization and are true contraceptives. - ^ 54.0 54.1 54.2 IUDs—An Update. Population Reports (Population Information Program, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health). December 1995, XXII (5).

- ^ IUDs—An Update: Chapter 2.7: Expulsion. Population Reports (Population Information Program, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health). December 1995, XXII (5). (原始内容存档于2006-09-05).

- ^ 56.0 56.1 IUDs—An Update: Chapter 3.3: Postpartum Insertion. Population Reports (Population Information Program, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health). December 1995, XXII (5). (原始内容存档于2006-04-29).

- ^ IUDs—An Update: Chapter 3.4: Postabortion Insertion. Population Reports (Population Information Program, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health). December 1995, XXII (5). (原始内容存档于2006-08-11).

- ^ WHO Scientific Group on the Mechanism of Action Safety and Efficacy of Intrauterine Devices, World Health Organization. Mechanism of action, safety and efficacy of intrauterine devices. Geneva: World Health Organization. 1987. ISBN 92-4-120753-1. hdl:10665/38182

. World Health Organization technical report series; no. 753.

. World Health Organization technical report series; no. 753.

- ^ Grimes DA. Intrauterine device and upper-genital-tract infection. Lancet. September 2000, 356 (9234): 1013–1019. PMID 11041414. S2CID 7760222. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02699-4.

- ^ Teal SB, Turok DK, Chen BA, Kimble T, Olariu AI, Creinin MD. Five-Year Contraceptive Efficacy and Safety of a Levonorgestrel 52-mg Intrauterine System. Obstetrics and Gynecology. January 2019, 133 (1): 63–70. PMC 6319579

. PMID 30531565. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003034.

. PMID 30531565. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003034.

- ^ Bahamondes L, Hidalgo M, Petta CA, Diaz J, Espejo-Arce X, Monteiro-Dantas C. Enlarged ovarian follicles in users of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and contraceptive implant. The Journal of Reproductive Medicine. August 2003, 48 (8): 637–640. PMID 12971147.

- ^ 62.0 62.1 62.2 62.3 62.4 62.5 Mirena. Bayer UK. 11 June 2013 [2015-06-18]. (原始内容存档于2015-06-18).

- ^ Donders GG, Bellen G, Ruban K, Van Bulck B. Short- and long-term influence of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena®) on vaginal microbiota and Candida. Journal of Medical Microbiology. March 2018, 67 (3): 308–313. PMID 29458551. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.000657

.

.

- ^ Nijhuis JG, Schijf CP, Eskes TK. [The lost IUD: don't look too far for it]. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde. July 1985, 129 (30): 1409–1410. PMID 3900746.

- ^ Kaplan NR. Letter: Lost IUD. Obstetrics and Gynecology. April 1976, 47 (4): 508–509. PMID 1256735.

- ^ Hormonal Contraceptives, Progestogens Only. International Programme on Chemical Safety. 1999 [2006-10-08]. (原始内容存档于2006-09-28).

- ^ Faculty of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care Clinical Effectiveness Unit. FFPRHC Guidance (April 2004). The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) in contraception and reproductive health. The Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care. April 2004, 30 (2): 99–108; quiz 109. PMID 15086994. S2CID 31281104. doi:10.1783/147118904322995474

.

.

- ^ Wong AY, Tang LC, Chin RK. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena) and Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depoprovera) as long-term maintenance therapy for patients with moderate and severe endometriosis: a randomised controlled trial. The Australian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. June 2010, 50 (3): 273–279. PMID 20618247. S2CID 22050651. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.2010.01152.x.

- ^ Bahamondes MV, Monteiro I, Castro S, Espejo-Arce X, Bahamondes L. Prospective study of the forearm bone mineral density of long-term users of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Human Reproduction. May 2010, 25 (5): 1158–1164. PMID 20185512. doi:10.1093/humrep/deq043

.

.

- ^ Ortiz ME, Croxatto HB. Copper-T intrauterine device and levonorgestrel intrauterine system: biological bases of their mechanism of action. Contraception. June 2007, 75 (6 Suppl): S16–S30. PMID 17531610. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2007.01.020. p. S28:

Conclusions

。Active substances released from the IUD or IUS, together with products derived from the inflammatory reaction present in the luminal fluids of the genital tract, are toxic for spermatozoa and oocytes, preventing the encounter of healthy gametes and the formation of viable embryos. The current data do not indicate that embryos are formed in IUD users at a rate comparable to that of nonusers. The common belief that the usual mechanism of action of IUDs in women is destruction of embryos in the uterus is not supported by empirical evidence. The bulk of the data indicate that interference with the reproductive process after fertilization has taken place is exceptional in the presence of a T-Cu or LNG-IUD and that the usual mechanism by which they prevent pregnancy in women is by preventing fertilization. - ^ ESHRE Capri Workshop Group. Intrauterine devices and intrauterine systems. Human Reproduction Update. May–June 2008, 14 (3): 197–208. PMID 18400840. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmn003

. 温哥华格式错误 (帮助) p. 199:

. 温哥华格式错误 (帮助) p. 199:Mechanisms of action

Thus, both clinical and experimental evidence suggests that IUDs can prevent and disrupt implantation. It is unlikely, however, that this is the main IUD mode of action, … The best evidence indicates that in IUD users it is unusual for embryos to reach the uterus.

In conclusion, IUDs may exert their contraceptive action at different levels. Potentially, they interfere with sperm function and transport within the uterus and tubes. It is difficult to determine whether fertilization of the oocyte is impaired by these compromised sperm. There is sufficient evidence to suggest that IUDs can prevent and disrupt implantation. The extent to which this interference contributes to its contraceptive action is unknown. The data are scanty and the political consequences of resolving this issue interfere with comprehensive research.

p. 205:

Summary

IUDs that release copper or levonorgestrel are extremely effective contraceptives... Both copper IUDs and levonorgestrel releasing IUSs may interfere with implantation, although this may not be the primary mechanism of action. The devices also create barriers to sperm transport and fertilization, and sensitive assays detect hCG in less than 1% of cycles, indicating that significant prevention must occur before the stage of implantation. - ^ Speroff L, Darney PD. Intrauterine contraception. A clinical guide for contraception 5th. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2011: 239–280. ISBN 978-1-60831-610-6. pp. 246–247:

Mechanism of action

The contraceptive action of all IUDs is mainly in the intrauterine cavity. Ovulation is not affected, and the IUD is not an abortifacient.58–60 It is currently believed that the mechanism of action for IUDs is the production of an intrauterine environment that is spermicidal.

Nonmedicated IUDs depend for contraception on the general reaction of the uterus to a foreign body. It is believed that this reaction, a sterile inflammatory response, produces tissue injury of a minor degree but sufficient to be spermicidal. Very few, if any, sperm reach the ovum in the fallopian tube.

The progestin-releasing IUD adds the endometrial action of the progestin to the foreign body reaction. The endometrium becomes decidualized with atrophy of the glands.65 The progestin IUD probably has two mechanisms of action: inhibition of implantation and inhibition of sperm capacite journal, penetration, and survival. - ^ Jensen JT, Mishell Jr DR. Family planning: contraception, sterilization, and pregnancy termination.. Lentz GM, Lobo RA, Gershenson DM, Katz VL (编). Comprehensive gynecology. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier. 2012: 215–272. ISBN 978-0-323-06986-1. p. 259:

Intrauterine devices

Mechanisms of action

The common belief that the usual mechanism of action of IUDs in women is destruction of embryos in the uterus is not supported by empirical evidence... Because concern over mechanism of action represents a barrier to acceptance of this important and highly effective method for some women and some clinicians, it is important to point out that there is no evidence to suggest that the mechanism of action of IUDs is abortifacient.

The LNG-IUS, like the copper device, has a very low ectopic pregnancy rate. Therefore, fertilization does not occur and its main mechanism of action is also preconceptual. Less inflammation occurs within the uterus of LNG-IUS users, but the potent progestin effect thickens cervical mucus to impede sperm penetration and access to the upper genital track. - ^ 74.0 74.1 Thiery M. Pioneers of the intrauterine device. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care. March 1997, 2 (1): 15–23. PMID 9678105. doi:10.1080/13625189709049930.

- ^ Thiery M. Intrauterine contraception: from silver ring to intrauterine contraceptive implant. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. June 2000, 90 (2): 145–152. PMID 10825633. doi:10.1016/s0301-2115(00)00262-1.

- ^ FDA drug approval for Skyla. (原始内容存档于2014-08-13).

- ^ Laitinen K. Bayer. businessfinland.fi. [2021-09-21]. (原始内容存档于2021-09-21) (美国英语).

- ^ 2009 Warning Letters and Untitled Letters to Pharmaceutical Companies. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. [2015-06-18]. (原始内容存档于2015-06-18).

- ^ 79.0 79.1 Bekiempis V. The Courtroom Controversy Behind Popular Contraceptive Mirena. Newsweek. 2014-04-24 [2015-06-18]. (原始内容存档于2015-06-18).

- ^ Budusun S. Thousands of women complain about dangerous complications from Mirena IUD birth control. ABC Cleveland. [2015-06-18]. (原始内容存档于2015-06-18).

- ^ Colla C. Mirena birth control may be causing complications in women. ABC 15 Arizona. 2013-05-21 [2015-06-18]. (原始内容存档于2015-06-18).

- ^ Bekiempis V. The Courtroom Controversy Behind Popular Contraceptive Mirena. Newsweek. 2014-04-24 [2016-11-16]. (原始内容存档于2016-11-15).

- ^ Popular contraceptive device Mirena target of lawsuits in Canada, U.S. CTV. 2014-05-21 [2016-11-16]. (原始内容存档于2016-10-26).

- ^ Blackstone H. When IUDs Go Terribly Wrong. Vice. 2016-05-31 [2016-11-16]. (原始内容存档于2016-11-17).

宮內節育器(俗稱"螺旋)。