User:Cypp0847/Testing2

| 伊莎貝拉及莫蒂默軍事行動 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

伊莎貝拉等人進攻路線以綠色標示, 愛德華二世等人撤退路線以啡色標示 | |||||||

| |||||||

| 参战方 | |||||||

| 親王派 | 逆眾派 | ||||||

| 指挥官与领导者 | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| 兵力 | |||||||

| 不明 | 1,500(入侵)[4] | ||||||

| 伤亡与损失 | |||||||

| 不明 | 不明 | ||||||

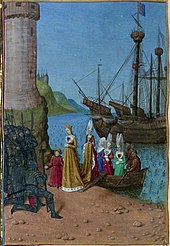

1326年,英格蘭王后法蘭西的伊莎貝拉連同情夫羅傑·莫蒂默入侵英格蘭,導致權傾朝野的小迪潘晨被俘虜、伊莎貝拉丈夫愛德華二世被廢黜,結束insurrection and civil war[2][3]。

背景

[编辑]羅傑·莫蒂默是位影響力巨大的邊疆貴族,與富有的嗣女妻子鍾·展維育有十二子女。1322年,莫蒂默被國王愛德華二世逮捕,之後被囚倫敦塔。莫蒂默的叔叔卓男爵在獄中逝世,而莫蒂默則成功在翌年越獄。他鑿壁後逃上天台,在友人協助下經繩梯跳入泰晤士河,最終抵達法國[5]。有維多利亞時期作者認為,伊莎貝拉有可能協助莫蒂默越獄,致使有歷史學家提出二人在此時之前已開展關係,不過暫未有確鑿證據證明二人在巴黎見面前已有穩定關係[6]。

1325年,阿基坦公爵兼太子愛德華前赴法國,向法國的查理四世行封臣臣服之禮[7]。伊莎貝拉偕同兒子赴法,王后就是在此行期間與莫蒂默發展關係[8]。伊莎貝拉的cousin埃諾伯爵夫人向莫蒂默介紹她,又提議愛德華太子娶伯爵夫人的女兒菲莉琶為妻,讓兩個家族聯婚[9]。同年12月起,伊莎貝拉和莫蒂默越漸親密。但在中世紀歐洲而言,已婚婦人不忠不貞乃是大罪,她的兩名sisters-in-law正正因此罪而被囚,最終在1326年逝世,亦即尼勞塔案[10]。因此,歷史學家深究伊莎貝拉為何敢於發展戀情,大多數人同意二人被對方深深吸引[11],其中一人更稱之為「中世紀最浪漫的愛情」[12]。二人不僅對亞瑟王傳奇有興趣,亦鍾情美術和富裕生活[11],以及憎恨愛德華二世政權和迪潘晨家族[2]。

1326年1月,伊莎貝拉向查理行完臣服儀式後,英王要求伊莎貝拉歸國。伊莎貝拉以流放曉·迪潘晨作為返國條件,但愛德華拒絕,繼而切斷所有對妻子的金錢援助[3]。伊莎貝拉轉而求助查理,但對方只准許她住在王宮,直至教宗若望二十二世表態反對伊莎貝拉,導致查理要求她離開,二人之後亦多年沒再交流[13]。1326年3月前,莫蒂默在英格蘭的支持者開始贈送二人食物和裝甲等[14],愛德華試圖阻截這些援助,並下令港口留意有否間諜滲入[15]。迪潘晨的權力亦日漸被挑戰,The authority of the Despenser regime suffered an increasing amount of rebellious acts including the audacious killing of the Baron of the Exchequer, Roger de Beler by Eustace Folville, Roger la Zouch and their gang.

伊莎貝拉與莫蒂默得不到法國的支持後,二人在1326年夏季帶同太子愛德華到神聖羅馬帝國,投靠埃諾伯爵威廉一世[13][16]。伊莎貝拉亦為太子與伯爵女兒菲莉琶訂下婚期[17],透過嫁妝招買僱傭兵,scouring Brabant for men, which were added to a small force of Hainaut troops.[18]。威廉亦給予伊莎貝拉八艘戰人軍艦和幾艘小型軍船,作為婚約一部分。Although Edward now feared an invasion, secrecy remained key, and Isabella convinced William to detain envoys from Edward.[18] Isabella also appears to have made a secret agreement with the Scots for the duration of the forthcoming campaign.[19]

入侵

[编辑]After a short period of confusion during which they attempted to work out where they had landed, Isabella moved quickly inland, dressed in her widow's clothes. A number of her key supporters immediately joined her, perhaps having been forewarned of her arrival, including the Bishops of Lincoln and Hereford.[20] Local levies, mobilised to stop them, immediately changed sides, and victims of the Despensers and relatives of Contrariants flocked to their cause.[20] By the following day Isabella was in Bury St Edmunds and shortly afterwards had swept inland to Cambridge.[21] Thomas, Earl of Norfolk, joined Isabella's forces and Henry, Earl of Leicester—the brother of the late Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, and Isabella's uncle—also announced he was joining Isabella's faction, marching south to join her. On 26 September, Isabella entered Cambridge.[22]

By 27 September, word of the invasion had reached the King and the Despensers in London. Edward issued orders to local sheriffs, including Richard de Perrers the High Sheriff of Essex, to mobilise opposition to Isabella and Mortimer, but with little confidence that they would be acted upon as he suspected that Perrers detested the Despensers.[20] London itself was becoming unsafe due to local unrest and Edward made plans to leave. Isabella struck west again, reaching Oxford on 2 October where she was "greeted as a saviour"—Adam Orleton, the Bishop of Hereford, emerged from hiding to give a lecture to the university on the evils of the Despensers.[21] Edward fled London on the same day, heading west toward Wales. Isabella and Mortimer now had an effective alliance with the Lancastrian opposition to Edward, bringing all of his opponents into a single coalition.[2]

Isabella now marched south towards London, pausing at Dunstable on 7 October. London was now in the hands of the mobs, although broadly allied to Isabella. Bishop Walter de Stapledon, unfortunately, failed to realise the extent to which royal power had collapsed in the capital and tried to intervene militarily to protect his property against rioters; a hated figure locally, he was promptly attacked and killed, his head being later sent to Isabella by her local supporters. Edward, meanwhile, was still fleeing west, reaching Gloucester by the 9th. Isabella responded by marching swiftly west herself in an attempt to cut him off, reaching Gloucester a week after Edward, who slipped across the border into Wales the same day.[23] Isabella was joined by the northern baronage led by Thomas Wake, Henry de Beaumont and Henry Percy which now gave her total military superiority.[20]

Hugh Despenser the Elder continued to hold Bristol against Isabella and Mortimer, who placed it under siege from 18 October until 26 October when it fell.[1] Isabella was able to recover her daughters Eleanor of Woodstock and Joan of the Tower, who had been kept in the Despenser's custody. By now desperate and increasingly deserted by their court, Edward and Hugh Despenser the younger attempted to sail to Lundy, a small island just off the Devon coast, but the weather was against them and after several days they were forced to land back in Wales.[24]

With Bristol secure, Isabella moved her base of operations up to the border town of Hereford, from where she ordered Henry of Lancaster to locate and arrest her husband.[25] After a fortnight of evading Isabella's forces in South Wales, Edward and Hugh were finally caught and arrested near Llantrisant on 16 November, which brought an end to the insurrection and the civil war.[26]

後續

[编辑]Edward II died somehow, most likely assassinated by orders of Isabella and Mortimer. What is known is that both Hugh Despenser the younger and Edmund Fitzalan were both hanged, drawn, and quartered. The deaths of Fitzalan, Despenser the younger, Despenser the elder and Edward II brought an end to the civil war, saw the start of a year of looting of the Despensers' estates and the issuing of pardons to thousands of people falsely indicted by them.[23]

On 31 March 1327, under Isabella's instruction, Edward III agreed a peace treaty with Charles IV of France: Aquitaine would be returned to Edward, with Charles receiving 50,000 livres, the territories of Limousin, Quercy, the Agenais and Périgord, and the Bazas country, leaving the young Edward with a much reduced territory.[27]

引用

[编辑]- ^ 1.0 1.1 Prestwich pp 86-87

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Lehman pp 141-42

- ^ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Richardson p 61

- ^ 4.0 4.1 Weir (2006), p 223

- ^ Weir (2006), p 153

- ^ Weir (2006), p 154; see Mortimer, 2004 pp 128-9 for the alternative perspective.

- ^ Ormrod, W. Mark. "England: Edward II and Edward III." The New Cambridge Medieval History. Ed. Michael Jones. Cambridge University Press, 2000. Cambridge Histories Online. Cambridge University Press. p. 278

- ^ Ormrod, p 287

- ^ Weir (2006), p 194

- ^ A point born out by Mortimer, 2004, p.140

- ^ 11.0 11.1 Weir (2006), p 197

- ^ Mortimer (2004) p 141

- ^ 13.0 13.1 Weir (2006), p 215

- ^ Patent Rolls 1232–1509.

- ^ Close Rolls 1224–1468.

- ^ Prestwich p 86 there was no danger from France for Isabella found her support from Hainaut

- ^ Kibler p 477

- ^ 18.0 18.1 Weir (2006), p 221

- ^ Weir (2006), p 222

- ^ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Fryde 1979

- ^ 21.0 21.1 Fryde pp 182-86

- ^ Weir (2006), p 226

- ^ 23.0 23.1 Fryde pp 190-92

- ^ Haines p 224

- ^ Wier (2006), p 234

- ^ Richardson p 643

- ^ Neillands, p.32.

文獻

[编辑]- Costain, Thomas Bertram. The three Edwards Volume 3 of History of the Plantagenets. Doubleday. 1962.

- Doherty, P.C.Isabella and the Strange Death of Edward II. London: Robinson. 2003. ISBN 1-84119-843-9.

- Fryde, Natalie. The Tyranny and Fall of Edward II 1321-1326. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1979. ISBN 9780521222013.

- Fryde, Natalie. The Tyranny and Fall of Edward II 1321-1326. Cambridge University Press. 2004. ISBN 9780521548069.

- Haines, Roy Martin. King Edward II: His Life, His Reign, and Its Aftermath, 1284-1330. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. 2003. ISBN 9780773570566.

- Lehman, Eugene. Lives of England's Reigning and Consort Queen. Author House. 2011. ISBN 9781463430559.

- Lumley, Joseph. Chronicon Henry Knighton I. London: HMSO. 1895.

- Mortimer, Ian. The Perfect King: The Life of Edward III, Father of the English Nation. London: Vintage Books. 2008. ISBN 978-0-09-952709-1.

- Neillands, Robin. The Hundred Years War History. Routledge. 2001. ISBN 9780415261302.

- Close Rolls. Westminster: Parliament of England. 1224–1468.

- Patent Rolls. Westminster: Parliament of England. 1232–1509.

- Prestwich, Michael. The Three Edwards: War and State in England, 1272–1377. Psychology Press. 2003. ISBN 9780415303095.

- Weir, Alison. Queen Isabella: She-Wolf of France, Queen of England. London: Pimlico Books. 2006. ISBN 978-0-7126-4194-4.

[[Category:英格蘭戰役]]

[[Category:1326 in England]]

[[Category:Conflicts in 1326]]

[[Category:入侵英格兰]]