论摩擦激起的热源

| 热力学 |

|---|

|

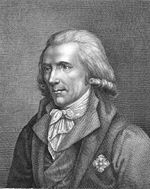

《论摩擦激起的热源》[1](英語:An Experimental Enquiry Concerning the Source of the Heat which is Excited by Friction[2],也称为伦福德的炮筒镗孔摩擦生热实验[3])(1798),是由伦福德最早发表在《自然科学会报》[4] 上的一篇论文,这篇论文向当时的热质理论抛出了一个重大难题,并引发了19世纪的热力学革命。

背景

[编辑]热质说是一种曾用来解释热的物理现象的理论。此理论认为热是一种称为“热质”(caloric)的流体物质,热质会由温度高的物体流到温度低的物体,也可以穿过固体或液体的孔隙中。

伦福德是热质说的反对者,他在当时经过研究后认为,所有的气体和液体都是绝对不导热的。由于他的观点过于超前,不被当时的科学界认可,并遭到约翰·道尔顿[4]和约翰·莱斯利[5]等人的批评。

由于伦福德受天主教的目的論論證[6]影响很深,他可能希望授予水某种特殊的导热权[4]。

尽管伦福德试图将热量与運動建立联系,不过没有证据表明他研究过分子运动论或是活力理论。

在这篇论文中,伦福德承认他曾认为热是运动过程的一部分[7]。这与弗兰西斯·培根[8]、罗伯特·波义耳[9]、罗伯特·胡克[10]、约翰·洛克[11]和亨利·卡文迪什[12]过去的一些观点不谋而合。

实验

[编辑]伦福德观察了慕尼黑兵工廠加农炮镗孔過程中摩擦生热的一些过程后进行了这个实验。他将一个加农炮筒浸入水中,并准备了一种特别钝的镗钻机。在这种情况下他不断的用钻机摩擦炮筒,钻出大量高热量的碎屑,并发现大概两个半小时后水沸腾了[1][2]。但问题在于,通过比较炮筒的比热容可以发现,这个过程中炮筒并没有损失能将水加热水平质量的物质来加热水,这与热质说的结论不符。

伦福德认为,看似无限的热量生成与热质理论不吻合。他认为在这个过程中唯一进行的操作只是运动和摩擦,因此他认为热不可能是物质而有可能是运动。

伦福德甚至粗略估计出产生1开尔文的热需要5.5焦耳的机械能,但他并未尝试进一步量化所产生的热量或测量热量的机械当量[3]。

影响

[编辑]

大多数当时的科学家认为热质说的确存在不完善之处,可以通过进一步完善该理论来适应该实验的结果,这一派科学家包括威廉·亨利[13]和托马斯·汤普森。此外,汤普森[14]、永斯·贝采利乌斯和安东尼·塞瑟发现了電似乎也能由摩擦“无限产生”。在当时没有一个科学家愿意承认电不是一种流体。

最终,伦福德声称的“无限生成”的热量被认为是该研究的鲁莽外推。查尔斯·海尔戴特批评,伦福德的实验可重复性十分差[15],整个实验看起来有一些偏见[4]。

然而,伦福德的实验给了焦耳灵感,1840年代焦耳再次精确的做了一次本实验,这次他用上了测定热量的仪器,最终在热质说的基础上建立了分子运动论这门科学。

参考文献

[编辑]- ^ 1.0 1.1 胡承正. 吉正霞 , 编. 热力学与统计物理学 (PDF) 第一版. 北京: 科学出版社. 2009-06: 1-2 [2020-07-24]. ISBN 9787030246042. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2020-07-24).

- ^ 2.0 2.1 Benjamin Count of Rumford (1798) "An inquiry concerning the source of the heat which is excited by friction," (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 88 : 80–102. doi:10.1098/rstl.1798.0006

- ^ 3.0 3.1 刘德磊、曾莉莉、屈志伟. 经典热力学发展概述. 《广州化工》. 2012年, (2): 26–28 [2020-07-24]. (原始内容存档于2020-07-24).

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Cardwell, D.S.L. From Watt to Clausius: The Rise of Thermodynamics in the Early Industrial Age. Heinemann: London. 1971: 99-102. ISBN 0-435-54150-1.

- ^ Leslie, J. An Experimental Enquiry into the Nature and Propagation of Heat. London. 1804.

- ^ Rumford (1804) "An enquiry concerning the nature of heat and the mode of its communication (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)" Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society p.77

- ^ From p. 100 of Rumford's paper of 1798: "Before I finish this paper, I would beg leave to observe, that although, in treating the subject I have endeavoured to investigate, I have made no mention of the names of those who have gone over the same ground before me, nor of the success of their labours; this omission has not been owing to any want of respect for my predecessors, but was merely to avoid prolixity, and to be more at liberty to pursue, without interruption, the natural train of my own ideas."

- ^ In his Novum Organum (1620), Francis Bacon concludes that heat is the motion of the particles composing matter. In Francis Bacon, Novum Organum (London, England: William Pickering, 1850), from page 164: (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) " … Heat appears to be Motion." From p. 165: (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) " … the very essence of Heat, or the Substantial self of Heat, is motion and nothing else, … " From p. 168: (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) " … Heat is not a uniform Expansive Motion of the whole, but of the small particles of the body; … "

- ^ "Of the mechanical origin of heat and cold" in: Robert Boyle, Experiments, Notes, &c. About the Mechanical Origine or Production of Divers Particular Qualities: … (London, England: E. Flesher (printer), 1675). At the conclusion of Experiment VI, Boyle notes that if a nail is driven completely into a piece of wood, then further blows with the hammer cause it to become hot as the hammer's force is transformed into random motion of the nail's atoms. From pp. 61-62: " … the impulse given by the stroke, being unable either to drive the nail further on, or destroy its interness [i.e., entireness, integrity], must be spent in making various vehement and intestine commotion of the parts among themselves, and in such an one we formerly observed the nature of heat to consist."

- ^ "Lectures of Light" (May 1681) in: Robert Hooke with R. Waller, ed., The Posthumous Works of Robert Hooke … (London, England: Samuel Smith and Benjamin Walford, 1705). From page 116: (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) "Now Heat, as I shall afterward prove, is nothing but the internal Motion of the Particles of [a] Body; and the hotter a Body is, the more violently are the Particles moved, … "

- ^ Sometime during the period 1698-1704, John Locke wrote his book Elements of Natural Philosophy, which was first published in 1720: John Locke with Pierre Des Maizeaux, ed., A Collection of Several Pieces of Mr. John Locke, Never Before Printed, Or Not Extant in His Works (London, England: R. Francklin, 1720). From p. 224: (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) "Heat, is a very brisk agitation of the insensible parts of the object, which produces in us that sensation, from whence we denominate the object hot: so what in our sensation is heat, in the object is nothing but motion. This appears by the way, whereby heat is produc'd: for we see that the rubbing of a brass-nail upon a board, will make it very hot; and the axle-trees of carts and coaches are often hot, and sometimes to a degree, that it sets them on fire, by rubbing of the nave of the wheel upon it."

- ^ Henry Cavendish (1783) "Observations on Mr. Hutchins's experiments for determining the degree of cold at which quicksilver freezes," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 73 : 303-328. From the footnote continued on p. 313: (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) " … I think Sir Isaac Newton's opinion, that heat consists in the internal motion of the particles of bodies, much the most probable … "

- ^ Henry, William. A review of some experiments which have been supposed to disprove the materiality of heat. Manchester Memoirs. 1802, (V): 603.

- ^ Thomson, T. "Caloric", Supplement on Chemistry, Encyclopædia Britannica, 3rd ed.

- ^ Haldat, C.N.A (1810) "Inquiries concerning the heat produced by friction", Journal de Physique lxv, p.213